Pinch Point #1

What it is, it's purpose, and how to do it right

I was diagnosed with Covid-19 after a week of feeling like I had allergies. As I’m writing this, most of my symptoms (body aches, congestion, etc) have gone, but my sense of smell and taste haven’t returned after these five days. I say that both as an excuse to why I haven’t been posting, but also as an analogy for what we’re going to learn about today.

We’ve already discussed the Inciting Incident and Plot Point #1 –- those two things are foundational, and speak to whether the script works at all, let alone works well. Those things are like my lungs. I need those to live, which is to say, do anything at all. My smell and taste, however, make my life less interesting and vivid, but aren’t necessary for survival, strictly speaking. This is also true of Pinch Points; you don’t need them for the script to work, but it’s a lot less interesting and vivid without them.

With that out of the way, let’s get to it.

* * * * *

Pinch Points, to paraphrase Karen Woodward, are a reminder to the audience of who the actual antagonist of a movie is.

She uses Stars Wars as an example of the first Pinch Point –– Episode IV: A New Hope, the audience is reminded that the Empire is in pursuit of the droids and the rest by their attack on the Falcon, etc. That was a big moment for me, as a screenwriter, because it unlocked my thinking on how to properly structure a script.

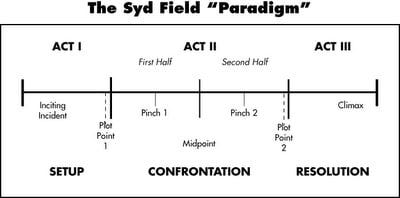

As a reminder, using Syd Field’s Paradigm, this is what much of screenplay structure looks like:

Pragmatically speaking, the Pinch Point serves to stop the first half of the Second Act from sagging. It gives the film something to build towards, so that for that (usually) half-hour first-half isn’t without stakes or consequences.

That sounds a lot like a Plot Point, right?

The key difference here is that it doesn’t spin the story off into a different direction. The stormtroopers attacking in Mos Eisley doesn't stop the Falcon and it’s crew from heading towards Alderaan. In Star Wars, this scene is almost entirely pragmatic –– meaning, that it’s hard to derive any kind of character or thematic subtext. To paraphrase Dennis Green, it is what what we think it is.

* * * * *

The breakthrough for me is that you can use that moment for a greater purpose. You need a moment around that time in the film to keep things moving and shaking, but without too much consequence. So, why not use that moment to bootstrap your theme and character right into the middle of things?

Imagine you were making a movie; a western, meant to be a blockbuster. Basic plot is as follows:

Sheriff Austin Dillon is an angry, violent lawman, who has made no friends over his long career.

He foils a bank robbery, earning the ire of the Chain Gang, a notorious band of thieves and killers.

They derail a train full of medical supplies, and frame the Sheriff for the accident. The townsfolk turn on him, and he barely escapes with his life.

He recuperates with the help of a local tribe, and he tames his anger and uses his newfound friendships to arrest the Chain Gang, expose their lies, and regain the respect of the town.

If you were to put that on the Paradigm, sans Pinch Points, it’d look something like this:

That mostly works, right? Clear beginning, middle, and end. Plot makes sense, if a little vague. But there’s not a lot there. It’s just a set of engineering drawings. There’s not life to it.

Now, if you add the Pinch Points, it looks something like this:

Just by adding those two Pinch Points, you solidify the character arc and theme. Instead of being a story about a police stopping crimes, it’s a story about a man learning to control his anger and work with others. The true antagonist of the piece is not the Chain Gang, but Sheriff Dillon’s rage. The first Pinch Point gives flavor and context to both Plot Point I and the Midpoint, giving that first 60 pages a deeper meaning.

* * * * *

Often, we’re trapped inside seemingly inescapable structure, a product of a movie needing to be, well, a product before it’s a work of art. But it doesn’t have to be that way. We can do both — make great art, have commercial success — without giving up one or the other.

I believe that character and theme are the way we do that — the way we have our cake and eat it, too — and Pinch Points are a vehicle to inject those things into any script. If I were to TL;DR this post, I’d say to think of Pinch Points as what the script is actually about, and everything else are the tracks in which we get there.